On September 15, the School of Science at Westlake University, together with the Zhang Biaobiao Laboratory and the Sun Licheng Laboratory of the Center for Artificial Photosynthesis and Solar Fuels, published a groundbreaking study in the top chemistry journal Nature Chemistry, unveiling a completely new mechanism for water oxidation.

They discovered that the nickel (Ni) active phase involved in the anodic reaction of water electrolysis can trigger a spontaneous oxygen evolution mechanism that proceeds without any external electrical input. This work adds a crucial piece to the puzzle of the “black-box” oxygen evolution mechanism in water electrolysis and provides an entirely new theoretical foundation for designing high-efficiency catalysts.

The bottleneck of hydrogen production through electrolysis of water

Hydrogen is regarded as a cornerstone of future clean energy systems, playing a pivotal role in the global energy transition and carbon neutrality goals. Electrolytic water splitting driven by renewable energy sources such as wind and solar offers a promising route for producing “green hydrogen” while simultaneously storing energy. However, the sluggish oxygen evolution reaction (OER) remains the efficiency bottleneck of water electrolysis. Elucidating the OER mechanism is therefore essential for designing advanced catalysts and enhancing hydrogen production efficiency.

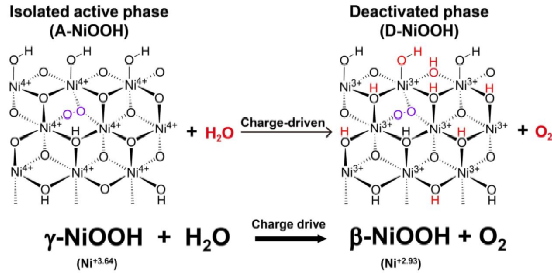

Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the isolation of A-NiOOH phase.

Found a string of bubbles

Normally, the release of oxygen must occur within an electrified circuit. However, Zhang’s team, by isolating the active phase of Ni-based catalysts formed under OER operating conditions—A-NiOOH—they observed that this phase can spontaneously release oxygen in pure water without any external bias, a phenomenon termed Spontaneous Oxygen Evolution (SOE).

Confirm the source of oxygen

Oxygen isotope labeling experiments further confirmed the oxygen source and revealed that the SOE process is driven by a lattice-oxygen coupling mechanism: oxygen is initially released through lattice oxygen coupling at the active sites, after which the sites continue to oxidize water, enabling sustained oxygen production.

Figure 2. Identification of the O2 release path and structural characterization.

Structure and Driving Force

Comprehensive structural characterization identified A-NiOOH as a γ-NiOOH phase containing Ni–O–O–Ni2 units that do not directly participate in oxygen release. The intrinsic driving force for SOE was attributed to the bulk-stored charges in Ni4+ species. Upon removal of the external bias, these charges can migrate from the bulk to the surface Ni active sites, thereby maintaining continuous water oxidation.

Figure 3. The reaction equation for the SOE of A-NiOOH with water to form D-NiOOH and oxygen.

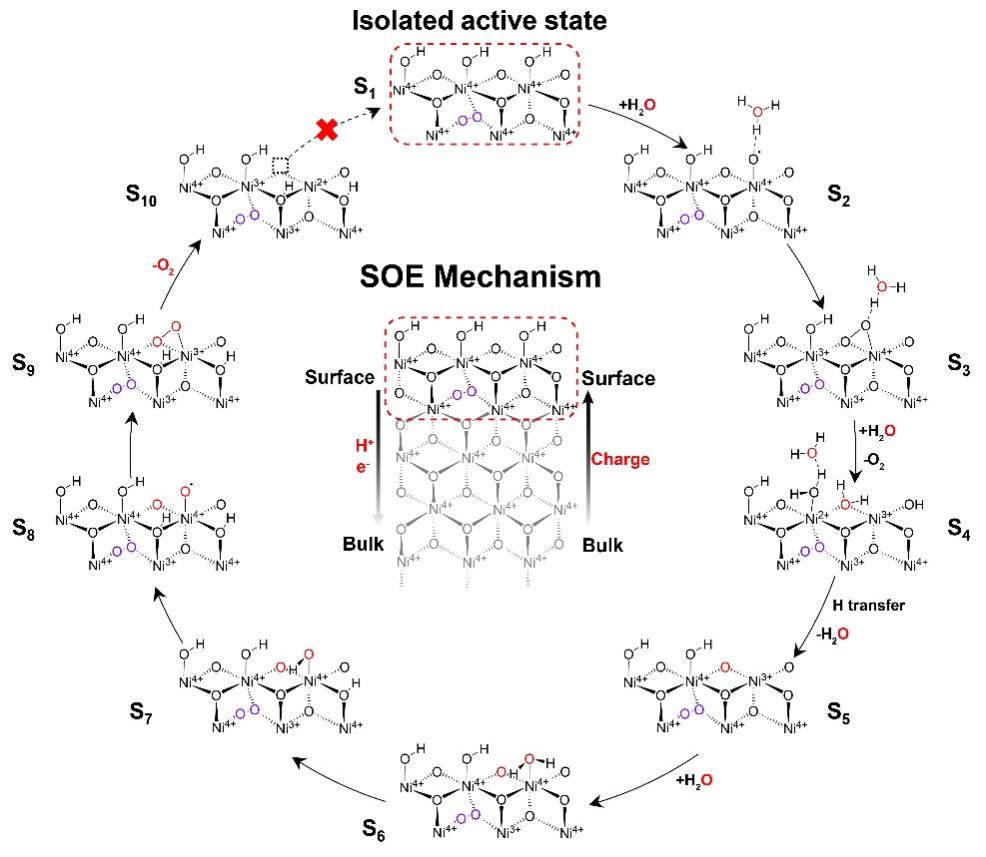

The “Trilogy” of SOE

The SOE proceeds through three sequential steps under the synergistic action of Ni4+ species and peroxo bridges:

1.Lattice oxygen evolution: On the A-NiOOH surface, the Ni4+–OH site first transfers a proton from a water molecule to generate an oxygen radical, which subsequently combines with a neighboring lattice oxygen atom to form O2, concurrently creating a lattice oxygen vacancy.

2.Re-oxidation of Ni sites: The release of lattice oxygen reduces the surface Ni species; however, the highly oxidized Ni in the bulk can re-oxidize the surface sites via charge transfer, establishing a self-sustained cyclic regeneration process.

3.Continuous water oxidation: The regenerated high-valent Ni sites facilitate a new cycle of water oxidation. The previously formed lattice oxygen vacancy and the Ni site respectively adsorb water molecules. After proton transfer into the bulk, two oxygen atoms couple and release a second O2 molecule. Driven by continuous charge migration toward the surface, the water oxidation reaction proceeds consecutively until the charge is depleted and the reaction ceases.

Figure 4. Catalytic pathway of SOE processes.

Mechanism of water oxidation in artificial photosynthesis

This work uncovers a previously unrecognized SOE mechanism in A-NiOOH, driven by the interplay between bulk Ni4+ charge reservoirs and peroxo bridges. The findings provide fresh insights into O–O bond formation and release pathways in Ni-based OER catalysts. Interestingly, the charge storage and release behavior shows conceptual parallels with natural photosynthesis, potentially offering new inspiration for understanding biological water oxidation.